There are clearly a range of ways that animal health and welfare researchers and policy makers can draw from psychology to improve the ways in which they communicate and/or elicit positive behaviour change in their target audiences. For example, psychology can help to improve our understanding of the influences on human behaviour; provide further insight on how individuals read and understand messages and explain why different types of messages interact with our personalities and our values.

This case study showcases our findings from two discourse analyses of pet and farm animal welfare guidelines. It also summarises findings from our human behaviour change work, namely the development of interventions tasked with changing or supporting animal health and welfare practices.

Stage

Directory of Expertise

Purpose

It is reasonable to assume that the gap between the best animal husbandry practice recommendations and their adoption will in some instances result from a failure in the communication process and/or a failure to identify the key determinants of competing behaviours. For example, it is possible that the messages that we use to communicate best practice are not fully understood or that they are not appropriately tailored to our target audiences (e.g., misaligning with people’s values and/or personalities).

To further explore whether a holistic approach to communicating best practices will more likely result in the adoption of those practices, our research draws directly from human behaviour science to identify the key barriers and drivers of behaviour. We also draw from the psychology of language and cognition research (e.g., framing [i]; language processing & working memory [ii]) and explore exactly how to improve the effectiveness of animal health and welfare messages to relevant stakeholders.

We believe that developing more effective ways to change behaviour may go beyond the scope of individual-level theories (e.g. the Theory of Planned Behaviour [iii],[1]), which in the past have been commonly adopted in the human behaviour and animal health/welfare literature. More recently, research that has explored the multifaceted underpinnings of behaviour using models, such as the Behaviour Change Wheel [iv] have proved more successful in eliciting positive behaviour change [v]. Going beyond the more individual level underpinnings of behaviour has of course proved most successful in the human health domain where health-related messages and behavioural support programs that consider the individual’s motivations, sub-conscious processes, emotions as well as the broader contextual influences, have resulted in more successful health campaigns e.g., smoking cessation [vi],[vii].

In considering the importance of psychology in aiding our understanding of human behaviour in animal health and welfare contexts, we have engaged in the following work:

Examining the determinants of human behaviour using the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCWiv) and the Comprehensive Messaging Strategy for Sustained Behaviour Change (CMSSBC [viii],[ix])

Examined the current animal health and welfare guidelines (e.g., RSPCA [x]) for key language styles, features and frames.

Examining the effects of plain language styles [xi] on pet owners and farmer’s perceptions of message effectiveness/friendliness.

Examining pet owners’ and farmers’ beliefs/perceptions of loss or gains-framed messages [xii],[xiii] in terms of their capacity to persuade the reader.

[1] Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) maintains that three core components, i.e. attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, work together to influence an individual’s intentions to act/behave. Intention is therefore key in terms of knowing whether someone will or will not engage in a behaviour iii. For example, if you wish someone to change their behaviour, they must evaluate the target behaviour positively (attitude), believe that significant others e.g. friends and family will approve of the behaviour (subjective norms), perceive that the behaviour is within their control (behavioural control) and the motivation to engage in the behaviour is greater than the motivation not to (intention).

Results

[1] Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) maintains that three core components, i.e. attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, work together to influence an individual’s intentions to act/behave. Intention is therefore key in terms of knowing whether someone will or will not engage in a behaviour iii. For example, if you wish someone to change their behaviour, they must evaluate the target behaviour positively (attitude), believe that significant others e.g. friends and family will approve of the behaviour (subjective norms), perceive that the behaviour is within their control (behavioural control) and the motivation to engage in the behaviour is greater than the motivation not to (intention).

Image: Person Holding Black & White Dog (Photo credit: Bekka Mongeau (pexels.com)).

Our overarching research is looking at how psychology can improve communication with animal caretakers and elicit positive behaviour change. This is being examined across seven different overlapping studies. The reason these seven studies were chosen is because past research has shown that plain language, framing, the Comprehensive Messaging Strategy for Sustained Behaviour Change (CMSSBCviii,ix) and the Behaviour Changeiv Wheel all prove relevant and important in eliciting positive human behaviour change within human health realms. We therefore believe these same approaches, models and frameworks may prove valuable for eliciting similar change to maintain/improve positive animal health and welfare practices. Our specific studies are as follows:

A discourse/framing analysis [1] of farm animal welfare guidelinesi

A discourse/framing analysis of companion animal welfare guidelines

A framing and plain language experiment with farmers

A framing and plain language experiment with pet owners

Human behaviour change science and body condition scoring of cattle using the Behaviour Change Wheel

Human behaviour change science and the management of painful procedures using the Behaviour Change Wheel

The application of the Comprehensive Messaging Strategy for Sustained Behaviour Change framework to animal health and welfare messages.

Framing Analysis of the Farm & Pet Animal Health & Welfare Guidelines

We first carried out a thorough discourse analysis of farm and companion animal health and welfare guidelines (studies #1 & 2), looking at features such as readability, analytical language style and framing. A frame essentially focuses our attention on one side of a story whilst obscuring another; affecting how that message is interpreted and acted upon,[i]. We thus analysed the farm animal and companion animal guidelines for a range of different frame types e.g., gain and loss-framed messages. A gain framed message focusses our attention on the possibility of a positive outcome and conversely a loss-framed message focusses our attention on a negative outcome. It is also thought we respond to gains and losses differently, with the belief that losses “loom larger” than gains thus persuading more people to act. However, how we respond to a frame is also dependent on our individual characteristics e.g. our aversion to, or like of, risk. Overall, we found evidence of both gain and loss frames used in both farm animal and pet welfare guidelines.

An example of a gain framed message in the farm animal health and welfare guidelines is as follows, “Good stockmanship, including frequent and thorough inspection along with correct diagnosis and implementation of a suitable programme of prevention and treatment, will help to reduce the incidence of lameness.” An example of a loss framed message was “Lameness is detrimental to animal welfare and a significant economic challenge for the sheep industry, with the overall cost to the industry estimated at £24 million a year”. The use of the different frames appeared to be somewhat unsystematic, suggesting that the frame type was not necessarily considered when communicating animal health and welfare messages. Interestingly, what we also observed was the loss framed messages were less likely to provide the reader with a solution to the problem but gain framed messages did. As we are more likely to respond to a message when signposted to a solution, this is an important factor to consider when writing guidelines[ii],[iii].

We also analysed the farm animal and pet guidelines for Plain Language Use xi, by measuring key language features such as sentence length and conversational or personalised styled language (i.e. using personal pronouns). A common myth around plain language is that it involves a “dumbing down” of the text to ensure that everyone can read and understand the message. However, plain language is a consideration of how best to connect with one’s reader. A key feature of plain language is therefore the use of personal pronouns to convey a more conversational tone. When a message is more conversational or personalised, we pay more attention to it and so these types of messages are more positively received and more easily remembered[iv],[v]. Overall, we found little evidence of a conversational style in the farm animal welfare guidelines. However, in the companion animal welfare guidelines, we did find some evidence of a conversational style in the dog [vi] and cat guidelines [vii]. Examples of conversational styled language are as follows, “Do you worry that your pet isn’t eating and give them tasty treats instead? Or do you always give in to those begging eyes as you eat your tea?” (Cats) and “Do dogs get the winter blues? Humans are often affected by the change in the seasons, with some suffering from seasonal affective disorder, but what about our dogs?” (Dogs). Conversational styled language was rarely or never adopted in both the rabbit and equid guidelines. It is possible given horses fall between companion animals and farm or working animals and rabbits fall between companion animals, pests and meat animals that we see such differences in language styles and message content.

We should also note that given the type and level of information that is needed in animal health and welfare guidelines it is of course unsurprising that a conversational style is not always adopted. However, we believe a conversational approach, alongside careful framing, could be considered in the future writing and development of guidelines. Adopting a psychology lens to help us understand how our audience will likely respond to a message as determined by how it is communicated over what is communicated may thus prove advantageous.

Human Behaviour Change Science & Communication

Drawing from the human behaviour change science, we also know that when we wish to elicit positive behaviour change through verbal or written communications not only should we inform people about what needs to change, why they need to change and how to change, but we must also consider what specific phase of change the person is in.viii,ix For example, does our reader know a problem exists? (detection phase) or do they know a problem exists but are unsure how to resolve it? (decision phase). It is extremely important when we communicate a message that we consider our audience might be in one of these phases of change. As the Comprehensive Messaging Strategy for Sustained Behaviour Change considers the message frame, the audience and the phase of behaviour change (e.g. a detection or decision phase of change), we have also adopted this framework in our human behaviour change intervention studies (5 & 6).viii, ix

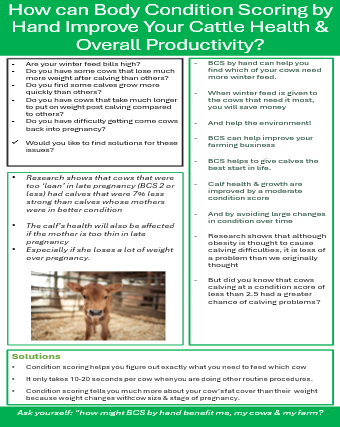

For example, in study #5, we adopted the Behaviour Change Wheel to develop an evidence-based intervention designed to encourage more cattle farmers to adopt body condition scoring by hand (i.e. our target behaviour). Past research has shown that despite knowing the advantages of this practice in terms of identifying lean and overweight cattle prior to calving, only 4% of farmers in the UK body condition score their cattle by hand [viii]. Our human behaviour change intervention mapping identified Education and Training as key intervention strategiesiii,[ix] and Guidelinesiii,[x] as effective ways to deliver these interventions. Thus, we believe drawing on the principles of CMSSBC to write the educational and training messages communicated via Guidelines, will ensure a more effective intervention. We have therefore drawn from the work carried out in studies 1, 3, 4 5, and 7 to create messages for farmers in each phase of change (i.e. detection, decision, implementation, and maintenance). In the detection phase, the person is unaware a problem exists. In the decision phase the person is aware of the problem but is deciding whether to act. In the implementation phase the person has decided to act but is seeking information/guidance on how to act i.e. looking for an action plan. In the maintenance phase the person is engaging in the target behaviour but is seeking guidance on how to continue with the behaviour and avoid relapsing into old habits or competing behaviours.

An example of a message template designed for someone in the “Detection” phase of change is illustrated below [2]:

In the detection phase, individuals are often unaware that a problem exists or that the problem holds some personal relevance to them. The message should therefore be clear, informative and concise. It is also important that we encourage the person to act because it will hold some personal value (i.e. intrinsic motivation) over using social influence or pressures (i.e. extrinsic motivation). The K-E document/guideline illustrated above thus contains some of the key features for the detection phase of change as recommended by the CMSSBC: 1. Identifies the problem, 2. Emphasises personal relevance to the reader and 3. Outlines quick & obtainable solutions. The message has also adopted the Plain Language Usexi features as discussed previously.

[1] Discourse analysis involves examining text to reveal the socio-psychological characteristics of the speaker(s). Discourse analysis examines the structure and expression of language against its social and cultural contexts. Framing analysis more specifically looks at how ideas, values, ideologies and beliefs are presented and reinforced in communication.

[2] This detection phase message has not yet been tested but will form an important part of our intervention in the next stage of our research.

Benefits

Many public policy interventions commonly work on the principle that raising awareness may change behaviour. However, as we have discussed, increased awareness does not necessarily translate into behaviour, with human behaviour being much less linear, and more complex by design. By drawing on psychology theory and human behaviour change science, we believe we can enhance our current communication and educational approaches, becoming more effective and consistent in eliciting positive change. We therefore believe psychologists may play an integral role in an interdisciplinary team tasked with increasing the knowledge and understanding of animal health and welfare and eliciting change across a wide range of contexts. We also propose that a more collaborative process between policy makers and an interdisciplinary research team of social and animal scientists may increase the use of evidence in policy making decisions [i].

Lead image: Body condition workshop in Speyside with Professor Simon Turner (Photo Credit: Lesley Jessiman, SRUC).

Project Partners

This research was funded by the Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services (RESAS) Division of the Scottish Government. We also want to thank the farmers and pet owners who have participated in our research to date.